Hi, friend. This is part five of my college series, where I share the challenges I faced during my time at UNC. If you haven’t already, you can catch up on the earlier posts here. I almost didn’t write this post because I’m still coming to terms with who I was at 21— I am not proud of my past actions. However, my hope is to do now what I couldn’t back then.

The late September sun casts a golden haze over Chapel Hill, its warmth seeping through the car windows. My sorority sister, Ashley, and I cruise down the highway toward a dress rental store 30 miles up the road in her sleek new Mercedes—a high school graduation gift. I had deliberately asked her to drive, desperate to avoid letting her see my old, beat-up Jetta.

“We’re on a mission,” Ashley declares. We are hunting for the perfect dress for her to wear to Old South, a fraternity event she’s been raving about for weeks.

Ashley and I became friends late in our freshman year at UNC—an alliance born more out of circumstance than deep connection. She is beautiful, charming, and socially entrenched in the Greek system—a ticket to the belonging I so desperately craved. In this world, proximity to the right people could mean the difference between blending in and being overlooked. Despite our vastly different upbringings—her world of country clubs and vacations in the Hamptons, and mine of modest middle-class familiarity—we rarely acknowledged the chasm between us.

Besides, by our sophomore year, friendships in our college circles had already solidified. I had to stay where I had landed.

Ashley hums along to a song on Spotify, tapping her manicured nails to the beat on the steering wheel. Her energy is exuberant; she has been looking forward to this errand all week.

I had never heard of Old South before coming to college, but Ashley quickly got me up to speed. The event is an antebellum-themed formal, typically held on a Southern plantation, where fraternity members of Kappa Alpha (KA) dress in Confederate-style military uniforms, and their dates wear 19th-century hoop-skirt dresses. Ashley is dating a boy, Matt, who is in KA at another university nearby. In a few weeks, she and Matt will head to Charleston with the fraternity to celebrate what she calls a “sacred tradition that has been around forever.” Or, more accurately since the 1920s.

Ashley is taking the entire thing way too seriously, but I wouldn’t dare point that out.

“The whole premise is to remember the Old South and its pre-Civil War era,” she explains, her voice tinged with pride. Her invitation had read, Let’s party like it’s 1865.

Unease prickles my skin. The racist undertones of the event are impossible to ignore, though they are neatly wrapped in the language of Southern pride. But Ashley isn’t bothered at all, so I wonder if I’m overreacting. I push down my discomfort and adopt her enthusiasm.

“I am so excited,” she says. “I need Matt to be blown away. I have to look like the epitome of a Southern belle.”

Ashley already looks like the epitome of a Southern belle. Her honey-blonde curls fall effortlessly around her face, always smooth, always shining. She is from Tennessee, from old money, and she carries herself like the debutante she once was. She has a way of making you feel seen—chosen—until you realize she makes everyone feel that way. I’ve been around her long enough to know that her sweetness is somewhat of a façade. I never want to land on Ashley’s bad side.

“You have to give me your honest opinion on these dresses, promise?” she says, amusement flickering in her tone. “It’s not like I know what antebellum dress style will look good on me.”

“You know I will,” I reply, though I’m baffled by her serious tone, completely oblivious to how absurd it all sounds.

“I’ve been to Charleston more times than I can count,” Ashley continues, “but I’ve never visited the Mills House Hotel. It’s famous because Robert E. Lee stayed there during the Civil War. He’s Kappa Alpha’s spiritual founder—this whole thing is sort of a way of honoring him.”

I hesitate. “Wasn’t Robert E. Lee… the leader of the Confederacy?”

“Yeah,” she says without pause. “But people give him a bad rep. I know what you’re thinking… but he was actually a really good man. A true Southern gentleman—the definition of chivalry.”

I nod, though my stomach coils with apprehension.

Ashley notices my silence and rushes to fill it with justification.

“Don’t worry, Sarah-Frances— It’s not like this is a celebration of slavery or anything. It’s simply about being proud of our Southern roots, keeping our traditions alive. We should be allowed to do that just like everyone else.”

“Ohhh, got it. I see,” I say.

But I don’t see.

I only know that questioning it feels like stepping too far outside the lines.

I turn to the window, letting the hum of the highway fill the silence.

It’s true, there are aspects of the South that I do love—its hospitality, its charm, the way cicadas hum at dusk. But this feels like something else entirely. Reenacting a time of deep turmoil in our country and honoring the general who fought to uphold slavery? It’s something I can’t reconcile.

I don’t know what to say, so I don’t say anything at all.

Silence has become my go-to survival tool, a well-practiced habit that keeps me connected to belonging.

When we pull into the beat-up rental store parking lot, the car’s AC gives way to thick, stifling air. The musty scent of aged fabric and dust hits us as soon as we step inside. The wooden floor creaks beneath my feet, and the dim lighting casts long shadows over racks of heavy satin and lace, making the space feel eerily frozen in time. A strange mix of reverence and unease settles in my chest.

Ashley approaches the woman at the counter with confidence.

“Hi! I’m headed to Old South,” she announces, as if this is something most people would recognize. “I’m looking for an antebellum dress, and I really want something that stands out. Something that pops, you know?”

I almost cringe at how ridiculous the whole thing sounds, but the woman behind the counter smiles, clearly eager for business and willing to help.

Ashley tries on hoop skirt after hoop skirt while I sit uncomfortably on a little purple bench outside the dressing room, offering my honest opinion. After what feels like an hour, she finally emerges in a light blue and yellow ball gown, its off-the-shoulder puffy sleeves adding to the dramatic effect. She has chosen a ginormous wide-brimmed hat, which the store clerk carefully ties under her chin with a ribbon.

She looks both ridiculous and perfect—as if she were Scarlett O’Hara herself, plucked straight from Gone with the Wind.

“Oh, wow,” I manage, struggling to find the right words. “That’s… definitely something.”

Ashley beams.

“I know. This is the one. We’ll take it!”

As soon as Ashley drops me off at my apartment, a wave of relief washes over me. The entire errand had been far more uncomfortable than I expected, and I feel dirty just for being a part of it.

I quickly jump into the shower, letting the hot water wash away the guilt of my complicity.

I imagine what it will be like for Black residents in Charleston to see Ashley and the fraternity boys parading around in their Confederate army uniforms, their giant hoop skirts—a look eerily reminiscent of plantation owners.

I feel sick to my stomach. What seems like a fun dress-up game to us could be traumatizing for others. I swiftly push the thought out of my mind.

I’m not going, so it’s not my problem. Justification settles the discomfort.

When Ashley returns from Old South a few weeks later, she won’t stop talking about how much fun she had. She thrusts her iphone toward me, swiping through pictures with pride.

“You should have seen the guys in their old uniforms. It was hilarious. They looked so cute. I love a man in a uniform,” she gushes. “We were like celebrities. People kept stopping to pose with us. They thought we were doing some kind of reenactment. It was such a hoot!”

Her voice fades into the background as I stare at the pictures.

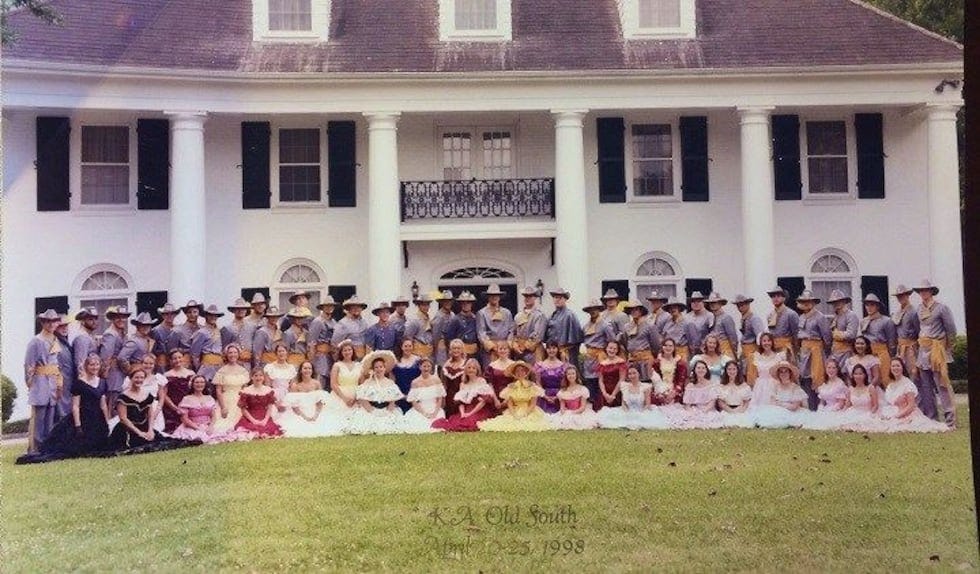

Fraternity brothers in Confederate uniforms, their faces stoic, standing in front of towering white columns on the plantation where the event was held—a symbol of dominance and power. Their dates kneeling neatly in front of them, hoop skirts fanned out like petals, giant smiles plastered across their faces.

A chill runs through me. It looks uncanny, like something plucked straight from a history book— As if the past is not the past at all.

I can’t look away.

The entire scene is deeply unsettling, and yet, no one else seems disturbed.

Ashley misinterprets my silence for disappointment.

“Aww, don’t worry, girl. I’ll make sure we find you a date next year so you can come too. I promise I won’t let you miss it!”

I imagine it—myself in one of those dresses, standing beside her, twirling through Charleston’s cobblestone streets, smiling like this isn’t something to question— like it isn’t something to grieve.

Disgust rises in my throat. It is thick and unrelenting.

The truth hits me all at once— I am no different than Ashley.

My absence from Old South does not absolve me.

My silence—my ability to look the other way—may actually be worse.

I’ve justified to myself that I am not a part of this, but I am.

I exist within a system that allows these traditions to persist, that insulates and excuses them. That celebrates them.

My silence is my complicity.

I feel as if I am going to be sick so I excuse myself to the bathroom, gripping the sink as I splash cold water on my face. I lift my head and stare at my reflection in the mirror.

Memories start to surface in my mind—fragments of a truth I’ve long ignored.

How many Confederate flags have I seen waved without shame in fraternity basements? How many times have I heard racist chants on bus rides to and from events? Why have I never questioned the overwhelming whiteness of my sorority?

Why did we casually refer to the only Black member as our “token black girl,” as if it were some badge of inclusivity?

The thoughts spin, unraveling, each one more horrific to bear.

I stand still for a few moments— suspended between two realities: the truth I can no longer ignore and the comfort of the world I refuse to confront.

I think of my parents—how disappointed they would be. This is not how I was raised.

Shame crawls up my spine.

When I walk back into the room, I feel a flicker of courage. I am going to confront Ashley.

I open my mouth to speak up, but the words don’t come.

Instead, I return to my seat on Ashley’s bed and continue looking at pictures from the weekend. I let Ashley’s bubbly chatter fill the room.

I am deeply ashamed of myself.

I wish I could speak up, but the fear of social exile, of standing alone, is just too great. Questioning traditions like this isn’t just uncomfortable—it’s dangerous.

Everyone knows there is an unspoken code in Greek life, a quiet understanding that we all follow: belonging is everything, and silence is the price of admission.

That night, I lie awake, staring at the ceiling, trying to justify my inaction.

I tell myself I’m overreacting—that I didn’t do anything wrong.

I wasn’t even at the event.

I repeat these excuses like a mantra, willing them to feel true— willing them to be enough.

I tell myself over and over again that staying quiet isn’t the same as agreeing.

But deep down, I know that’s a lie.

As the months pass, it’s a lie I learn how to live with it. How to smile and nod. How to laugh when I’m supposed to. How to pretend I don’t hear the things that make my stomach turn.

The more I ignore the discomfort, the more natural it becomes.

However, the weight of my silence never really leaves me. It always lingers, pressing against the edges of who I thought I was, who I wish I still had the courage to be.

I watch myself become more and more like Ashley—not because I don’t see the truth, but because it’s easier. Because it’s safer.

Because pretending is what keeps me in the club.

Every time I choose the comfort of complicity over the risk of speaking up, I let go of another piece of myself.

I feel it—this slow erosion, this quiet disappearing.

And I hate myself for it.

**Click here to read the next post in this series!!

Oof… thank you for sharing your personal history and for processing it so publicly. You were harmed by white supremacy as well; it may serve the interests of a few but ultimately hurts all of us. For what it’s worth, I think you are doing an enormous amount of good with this content, including healing yourself. Keep going.

I hope you can offer your younger self more compassion- what a hard experience. Seems like you are actively working on voicing your disgust for it all now. Thanks for sharing!